When people commandeered airplanes to destroy the World Trade Towers on September 11, they did it in the visual language of Hollywood, making it the most photographed event in the history of the world. They used the money-making visual language of action films that the United States had exported throughout the world against the country that had invented it.

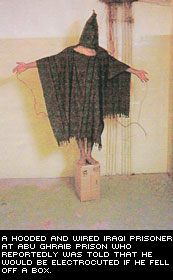

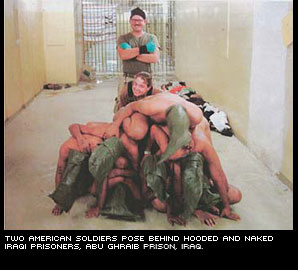

Now, ostensibly responding to the imagery of the abuse at Abu Ghraib prison, a group of people in Iraq just beheaded a young American, Nick Berg, on videotape as others had done in Pakistan previously to Daniel Pearl. Now Palestinians are keeping the body parts of Israeli soldiers in Gaza. Those without power are striking back with grotesque visuals. It is an insane imagery, made unfortunately familiar by the horrific photographs of the lynching of African-Americans by jeering, picnicking whites earlier last century. The pandora’s box of cruelty has now been made visible, opening and re-opening the deepest of wounds.

|

|

Meanwhile, in case you missed the new bill before Congress, reported by the AP on May 11 in an article entitled “Congress Looking at ‘Video Voyeurism’”:

-

“The bill before Congress would make it illegal to videotape, photograph,

film, braodcast or record a naked person or someone in underwear anyplace

where ‘a reasonable person would believe that he or she could disrobe

in privacy.’

“The legislation also would make it illegal to sneak photos of a person’s ‘private parts’ when ‘their private parts would not be visible to the public, regardless of whether that person is in a public or private area.’

“A person convicted under the law could face a fine and as much as a year in jail.

“The bill passed the Senate by voice vote without dissent. The House Judiciary Committee is expected to consider it before the August recess.”

In Abu Ghraib the problem is the actions by members of the US armed forces, not the photography (although there are many Americans wishing that these photographs never saw the light of day). Without the photography we would not know about the degradation of forcing prisoners to simulate oral sex or masturbate for the camera. Of course, the photographers who provided these pictures would now be liable for “sneak[ing] photos of a person’s ‘private parts,’” and could face a fine and up to a year in jail.

| |

|

Or perhaps this latest legislation is just a symptom of a deep confusion in the United States, accustomed and disoriented as it now is by “reality tv,” as to what should be made visible or invisible other than a woman’s underwear. As we have seen in this last couple of years, the underside of a woman’s skirt is not the only thing that the US government has deemed off limits. The use of “embedded” photojournalists to show a heroic US military in Iraq, the pictures dispatched almost immediately after each action, can now be even more aggressively questioned as an exercise in propaganda. While one should probably assume that the great majority of US troops acted with the utmost concern for battlefield rules, why is it that all these hundreds of journalists came up with a scenario of the Iraq War as a replay of World War II’s battle of good against evil with hardly a transgression?

The images from Abu Ghraib prison show that the US military has not always done the right thing, just as many of the lacerating images from the Vietnam War by Don McCullin and Philip Jones Griffiths, among others, showed that crimes against humanity occur all too often during war. The staged photo opportunity of pulling down the Saddam Hussein statue by US troops was made to symbolize an otherwise largely invisible uprising by the Iraqi people; Colin Powell’s use of satellite imagery to “demonstrate” the existence of weapons of mass destruction before a skeptical United Nations was highly useful to sway a skeptical world; similarly George Bush’s appearance as airplane pilot on the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln under the banner “Mission Accomplished,” or his Thanksgiving appearance in Baghdad with a decorative turkey as if he were personally feeding the troops, served to camouflage that chaos in Iraq. All of these and many more image deceptions have left the United States and the world with a deep unease as to what exists behind the theater of image.

But these strategies of fabrication finally collapsed. It took an employee’s photographs of the multiplying caskets of American soldiers and a freedom of information request from a tiny Web site, www.thememoryhole.org, to let Americans see some of the costs of war. (The woman who took the photos was fired, as was her husband for good measure.) And the reluctance of American newspapers to publish the photographs of those Americans killed in war turns out to have been cowardly, as Ted Koppel showed when Nightline finally went on air with the photographs of the hundreds of casualties from the first year in Iraq.

It is also the same year when someone tried to composite two photographs together to place John Kerry and Jane Fonda as speaking together at an anti-Vietnam War rally, when they never did. Unfortunately, several publications ran the “photo,” not having thought to check its authenticity first. The importance of safeguarding the photograph as evidence of actual events has never been more important, as the images from Abu Ghraib make clear.

This is also the same year when people in the United States will have to elect a president. One hopes that, if not transparency, at least we can expect the accountability that comes with visibility. It is apparently too difficult, even for the world’s superpower, to continually orchestrate the state of the world in its own image.

- Fred Ritchin

May 12, 2004

We invite anyone interested in submitting a response to "The Horror, The Horror" by emailing to response@pixelpress.org

In addition to your comments, we will also publish your name and the city or country where you live.

Due to the volume of submissions, we may not be able to publish all materials. We reserve the right to edit your response for clarity.