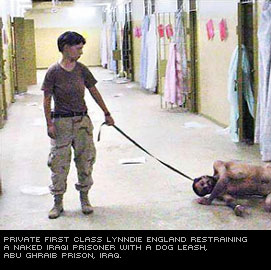

If awards were to be given for the Most Important Photographs of 2004, certainly the photographs from Abu Ghraib prison would rank high on the list. As would the photographs of the caskets of American soldiers killed in Iraq; or the photographs of one year’s American war dead, shown on ABC television; or the photographs of the crowd reveling in the deaths of the four Americans in Falluja.

Interestingly, it would only be the images from Falluja that were made by professional photojournalists. The others were made by amateurs, including soldiers and an employee of a Pentagon sub-contractor, or were simple identity photographs.

|

And if an award was to be made in the category of Photo Illustration, the image of John Kerry and Jane Fonda together on a podium giving anti-Vietnam War speeches would be a contender – if the identity of the person who composited the two separate photographs together were to become known. Another contender would be the images of British troops supposedly abusing Iraqi prisoners that were later found out to have been staged.

|

The grisly decapitation of Nick Berg would have to be considered one of the most important if horrific short documentaries in the Video category. Again, it was made by a non-professional photographer.

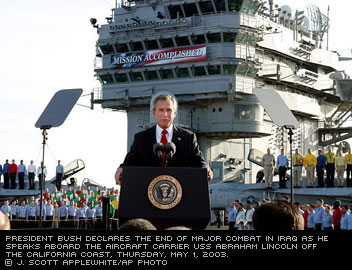

Ultimately any of the amateur-produced news photographs mentioned above did more to peel off layers of hype concealing the war effort and its sometimes catastrophic results than did any photography done by the “embedded” photojournalists, representing professional news organizations from around the world. Baghdad in flames? American troops in a firefight? Saddam Hussein’s statue being toppled? Perhaps some of the imagery of injured civilians began to get at the deeper realities of war. But for the most part the professionals seem, often unwittingly, to have become part of a major public relations campaign to make the war in Iraq appear to be a crusade for good against evil.

The increasingly widespread use of digital cameras – creating images that do not need to be processed in labs where they can be censored but instead can be immediately uploaded by the photographer and transmitted on the internet – have many arguing that a new age of openness is upon us. Governments will not be able to hide the multiple truths of war, or anything else, as they once did. The exclusion of professional photographers from the first Persian Gulf War, then the decision to “embed” them in the Second, has now led to a “return of the repressed” – a Vietnam War-style depiction of war as at times horrific. Except that those operating the cameras most effectively are often amateurs.

For professionals, life is not getting easier. The decision to “embed” photographers effectively diminished the independence of the press corps. Who wants to make critical images of the people who are essential to one’s survival on the battlefield? The increasing danger of covering conflicts where journalists are targeted (not just in Iraq, but all over the world) forces photographers to seek sanctuary as “embeds” or travel in groups for their own protection. But as the professional photographer became beholden to the military for access and safety, and responsive to back-home publications that wanted to tell the war in a “patriotic” way, some critical judgment seems to have been ceded. The multiple books and exhibitions that came out after the American “victory” seem both superficial and misguided one year after “mission accomplished.”

|

It is the amateurs with their digital cameras, feeling freer in their image-making, who came up with the most compelling, painful and shocking imagery, at least for the moment. Undoubtedly the military will soon ban cameras for soldiers. Instead, officially sanctioned army photographers will make the images to send home to families and friends. Professional photojournalists will be kept as far away as possible from sensitive areas like prisons and burials. And legions of people will, like the faked “photographs” of British troops abusing Iraqis, attempt to create the most damning photo-composites or staged images possible to attack whomever and whatever it is they want to.

But the major lesson seems to be that if one wants to communicate with many people, the best thing is to bypass conventional media. Go on the Internet. There is a perception that contemporary media is too filtered, too tired, too constrained by advertising and by governments. Just this week it was reported that a powerful editor, Graydon Carter of Vanity Fair, accepted $100,000 for a movie idea from the same Hollywood people his magazine supposedly covers. Numerous reporters and photographers have been fired over the last year for various well-publicized manipulations of the press. Given these developments, the unfiltered directness of the Internet can be seen as refreshing.

But of course media on the internet can be highly manipulated as well. The Kerry-Fonda faked photo-composite is but one example of the possibilities for a large political impact based upon false information. As Ken Light, the author of the John Kerry half of the composite, pointed out: What if such a fabrication were to be published a few days before the US elections in November? By the time the fabrication was uncovered, would more people have voted for George W. Bush? Might he win the national elections in part because of such fakery, considering that he won the last election by only some 600 votes.

The amateur digital photographers, and not their professional colleagues, are the ones who have managed to reach the hearts and minds of so many people around the world. Their future at the center of media seems assured, at least for the moment, as the world waits for the newest revelations from Abu Ghraib and elsewhere.

But what then is the future for the professionals?

- Fred Ritchin

May 16, 2004

We invite anyone interested in submitting a response to Photography's "Amateur Hour" by emailing to response@pixelpress.org

In addition to your comments, we will also publish your name and the city or country where you live.

Due to the volume of submissions, we may not be able to publish all materials. We reserve the right to edit your response for clarity.