|

|

|

At

around 1300, exactly one week after the mortar attack that killed

Lance Corporal Vincent Sullivan, five to six mortar rounds were fired

at Camp Iskandariyah. They landed in a lightly trafficked spot and

injured no one.

"A white Kia Bongo 2-door [truck] was the vehicle spotted at

the mortar position," reads today's Iraqi National Guard log translated

from Arabic and provided by the Marines. "Badger 2", working

with other Marine patrols, tracked down the suspect truck to a nearby compound. "Badger

2 reports that they have one full mortar system," the Marine's

logbook says. Three men were taken into custody, according to Staff Sergeant Edward

Palacios, the leader of the raid. "We hit some pay dirt today,"

another MARINE back at the operations center told me.

Palacios, a laconic young Texan with eight years in the Corps, and

a respected unit leader, took me on my first patrol last week. He

sounded relieved tonight, a few hours after the raid, but he wasn't

celebrating. "Out here I really don't have any feelings. I'm

just glad

we caught the ones who fired on us today. Hopefully, it slows things

down, even though I know it won't. We've just got to get our heads

together and go out and find more."

Iskandariyah and the surrounding towns I have visited or cruised through

on Marine patrols are sundered, battered places. Most of the one-

and two-story cement and cinderblock buildings are crumbling and askew.

Saddam Hussein's ruthless divide-and-dominate policies crushed this

country, destroying among other things the bonds between citizens.

The lingering post-Saddam violence retards healing, reconstruction,

and the rebirth of community. Neighborhoods continue to decay, and

few citizens feel safe enough to begin serious rebuilding.

Many feel it is best to concentrate on what you can control, the life

behind the closed doors of your home, than to take a public stand

that might draw the attention of the dangerous, and often murderous,

forces that equate reconstruction with capitulation to the American

agenda. There are some who take that risk, but they are the minority.

USMC's Civil Affairs Group is a small operation charged with funding

infrastructure projects -- sewage, water, school reconstruction --

as well as training and equipping the new Iraqi Police (the IP), and

supporting local governing bodies. CAG has spent roughly $2 million

on these endeavors over the past six months. Major Tom West runs that

effort for this area, North Babil. "I play police chief, mayor,

business contractor, adviser to clinics and hospitals," the 37-year-old

reservist told me.

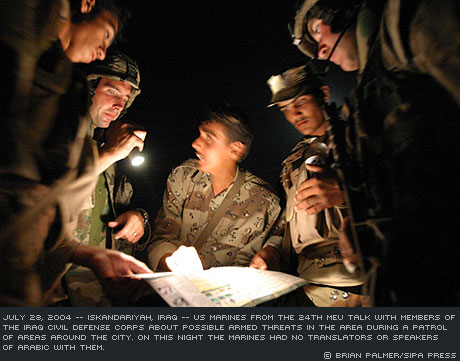

West gets backup from CAG's host unit, the 24th Marine Expeditionary

Unit, which is the biggest economic and military power in the area. But

this isn't the USMC's primary mission -- restoring "security and stability"

with military force is -- and it's not where the greatest share of their

time, energy, and personnel are committed. Still, the hearts-and-minds efforts

of CAG, the MEU, and the Army, which served on this base before the Marines,

embody the Bush administration's promises to rebuild this fractured

nation.

This week CAG ventured into town to inspect a water project it is

funding through the Iskandariyah City Council. Now that Iraqis have sovereignty

over their affairs, nominal as it is, things work this way. The City Council

chooses the contractors -- but the Marines oversee the bid process,

review tenders, and bankroll the work.

This project was a modest effort in an isolated and remarkably intact

neighborhood of forty households. A council member, the contractor,

and his workers showed the CAG staff their progress, a partially drilled well

and a half-finished concrete platform for a water tank. "Is this water

project going to benefit all 40 families?" asked the CAG's project manager,

Sergeant Jesus Jacquez, working his way through a list of obligatory

questions. Several Iraqi men in the entourage said yes, it will.

An unsmiling heavyset older man, Hazim Tahir, joined our knot of people

along with a group of curious residents. He spoke in crisp, British-flavored

English. I asked him how he felt about the water project. "The

last people who came here" -- the Army -- "stayed for two months, then

they left," said an agitated Hazim, an engineer with the Ministry for Science and Technology

who studied in England. "You want to do it, " he told me,

"do it. If you don't, don't promise." He was close to tears, and shuddering

with anger. "All you can do is protect yourself," he said of US forces, "then

go home." |

|

|

|