|

|

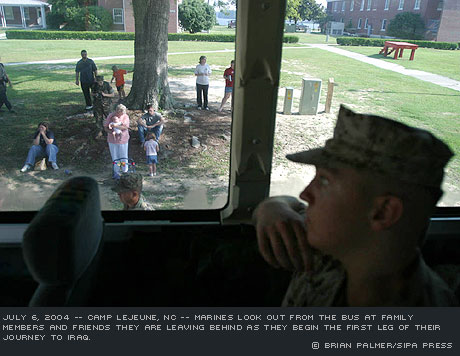

Just

a few family members and girlfriends have gathered at Camp Lejeune,

NC, to send off the Command Element, the only piece of the 24th Marine

Expeditionary Unit that is still Stateside. The entire MEU (sounds

like chew), about 2200 men and women, will reassemble in Kuwait, then

train in the desert to acclimate to the region. The artillery battery

will shoot its 155mm howitzers. The transportation folks will practice

driving and securing vehicle convoys with live ammunition. Everyone

will rehearse the basic, armed foot patrol. This is preparation for

a seven-month deployment to Iraq.

A civilian woman and a young male Marine cling to each other, whispering.

It's excruciating to watch but turning away is just as hard, I say

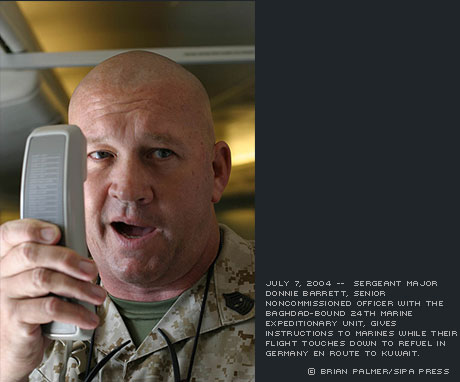

to Sgt. Major Donnie Barrett, the MEU's highest-ranking noncommissioned

officer. A towering, refrigerator-size man who cuts a less-than-cuddly

figure in his desert camouflage fatigues, he nods in agreement. Barrett,

who joined the Marine Corps 25 years ago, volunteers that he won't

let his wife come out to the base to say goodbye anymore. It's too

painful, and it never gets any easier, he says.

A staff sergeant barks a set of instructions. The Marines shoulder

their unwieldy packs and jam them into the buses' baggage holds. They

load office equipment and their own canvas seabags onto a five-ton

truck. Then the vehicles pull away, leaving behind a handful of subdued

loved ones.

A MEU is a self-contained fighting unit, a quickly deployable strike

force comprised of infantry, support, aviation, and command components.

This MEU takes over "security and stability" operations

in an area south of Baghdad in mid-July from a departing US Army unit.

More than half the Marines in the 24th MEU, some of them in their

late teens and early twenties, served in Iraq just one year ago. The

members of the infantry arm of the MEU, First Battalion/Second Marines,

still talk about the brutal battle at An Nasiriyah, where they lost

18 men, at least one to friendly fire from an aircraft.

Marines have been dispatched around the world by successive US presidents

in configurations like the MEU to give force to a variety of policies.

Administrations say, Jump, and the Marines do just that. Or as a MEU

commander told a reporter and me 10 years ago: "We kill people

and blow things up."

That crude -- and accurate -- statement floored me. It also changed

my life. I was a crunchy Brown University graduate who hadn't served

in the armed forces. In fact, I never had any interest in joining

up. Vietnam War footage I watched on my family's black-and-white TV

as a kid terrified me. Over the years I absorbed the belief, pervasive

in some parts of American society, that the armed forces were something

to be protested -- or ignored.

Another crucial factor: My father served in the Army during the Korean

War, which was just a couple of years after President Truman ordered

the armed forces to mix its all-black and all-white units. Truman's

desegregation proclamation, however, didn't magically transform the

hearts and minds of the white servicemen who attacked and beat my

father and his squad, black men, for simply getting "too friendly"

with a couple of German waitresses. "Never join the white man's

army," my father, the former sergeant, warned, seething.

But the military I covered in the early 90s was not my father's military.

The racial dynamic on the ships on which I sailed was similar to what

I saw and lived elsewhere in the US; it was a work-in-progress. I

stumbled into pockets of matter-of-fact racial and ethnic harmony

aboard the USS America and the USS Guadalcanal, even as I noted the

scarcity of colored folks in command meetings.

More profoundly, though, the MEU commander's blunt statement -- and

the month I spent aboard US Navy ships photographing Marines and sailors

-- made me realize that my reflexive mistrust of the military was

pointless, irresponsible, and self-indulgent. The military simply

is. The armed forces are a tremendously powerful tool that has been

misused by Presidents -- and used constructively and heroically by

some administrations as well. Understanding the military -- what it

is, what it has done, and what it can do -- is a citizen's responsibility.

This is, I realized, is a form of patriotism, which isn't just waving

the flag and supporting every move the president makes. Nor is it

opposing every step of the guy you didn't vote for, but who got elected

anyway. Patriotism, in my view, means participating in the shaping

of this nation and holding our leaders accountable for their actions.

|

|

|

|